“[T]here is nobleness in the name of Edmund. It is a name of heroism and renown; of kings, princes, and knights; and seems to breathe the spirit of chivalry and warm affections.” — Mansfield Park, by Jane Austen, chapter 22.

Edmund Bertram is intelligent, generous, principled, and affectionate. He is not afraid to take the initiative in doing what he thinks is right. He has many good qualities and, of course, some faults. Of these characteristics, I think one of those which most defines him — the quality which most sets him apart from others and earns him the status of hero — is his quiet, unobtrusive kindness, especially in all the small (and sometimes not-so-small) ways he silently cares for the heroine, Fanny Price.

When, as a sixteen-year old young man, Edmund finds his newly-installed little cousin Fanny crying on the attic stairs, he speaks to her “with all the gentleness of an excellent nature” (ch. 2), calming her feelings of embarrassment at being so discovered and persuading her to confide her sorrows. Finding that she is, naturally, missing her family, he helps her write a letter to her brother William. He finds her an undisturbed place in which to write, procures her writing materials, rules her paper for her, sharpens her pen, helps her with her spelling, and delights her by adding a note of his own for William and sending him half a guinea under the seal. This is only the beginning of Edmund’s kindnesses to Fanny:

“Without any display of doing more than the rest, or any fear of doing too much, he was always true to her interests, and considerate of her feelings, trying to make her good qualities understood, and to conquer the diffidence which prevented their being more apparent; giving her advice, consolation, and encouragement.” — Chapter 2, italics mine.

Time and again, he protects her, serves her, and makes sacrifices for her. When the pony Fanny rode for her health dies during her uncle’s absence in Antigua, Edmund insists, “Fanny must have a horse.” (Ch. 4.)1 Although he could not help paying heed to his aunt’s caution against increasing his father’s stable expenses,2 he “could not bear [Fanny] should be without” this means of exercise, so he determines to give up one of his own horses (no small gift) that it may be exchanged for a mare for her especial use. Fanny is delighted with the mare, finding, to her surprise, even greater pleasure in riding it than she had had with the pony.

Learning that newcomer Mary Crawford wishes to learn to ride, Edmund asks Fanny’s leave to use the new mare. When Mary desires to use the mare for a whole morning, Edmund tells Fanny, “[A]ny morning will do for this. … She rides only for pleasure, you for health.” (Ch. 7.) Despite his caution, however, more and more riding parties are planned, with Miss Crawford borrowing the mare. Then, one day, Edmund finds Fanny with a headache from walking in the sun at her aunt’s behest. Realizing that she has been without choice of exercise or excuse for avoiding her unreasonable aunt’s requests, he is immediately angry with himself and resolves that “however unwilling he must be to check a pleasure of Miss Crawford’s [with whom Edmund “was beginning … to be a great deal in love”] that it should never happen again.” (Italics mine.) The next chapter begins: “Fanny’s rides recommenced the very next day …” (ch. 8).

Learning that newcomer Mary Crawford wishes to learn to ride, Edmund asks Fanny’s leave to use the new mare. When Mary desires to use the mare for a whole morning, Edmund tells Fanny, “[A]ny morning will do for this. … She rides only for pleasure, you for health.” (Ch. 7.) Despite his caution, however, more and more riding parties are planned, with Miss Crawford borrowing the mare. Then, one day, Edmund finds Fanny with a headache from walking in the sun at her aunt’s behest. Realizing that she has been without choice of exercise or excuse for avoiding her unreasonable aunt’s requests, he is immediately angry with himself and resolves that “however unwilling he must be to check a pleasure of Miss Crawford’s [with whom Edmund “was beginning … to be a great deal in love”] that it should never happen again.” (Italics mine.) The next chapter begins: “Fanny’s rides recommenced the very next day …” (ch. 8).

Caught up in ideas for improving Sotherton, the young people, under the management of Mrs. Norris, plan an outing there. The latter arranges who will go in the carriage, who on horseback, and who — namely Fanny — will stay at home with Lady Bertram. Everyone concurs except Edmund who “heard it all and said nothing” (ch. 6). He says nothing, but quietly makes arrangements to stay at home himself so that Fanny, whom he knows to have “a great desire to see Sotherton” (ch. 8), may go instead. In the end, Mrs. Grant offers to spend the day with Lady Bertram so that Edmund and Fanny may both go — earning the gratitude of each as Fanny, though grateful for Edmund’s kindness, was pained “that he should forgo any enjoyment on her own account” and felt that she wouldn’t enjoying seeing Sotherton without him, and Edmund “was very thankful for an arrangement which restored him to his share of the party”.

Edmund does his best to overcome his family’s habit of using Fanny to run errands.3 Although not completely successful in stopping this practice, Edmund quietly steps in to curtail it when he can. On one occasion, when Lady Bertram, from her sofa, tells Fanny to “ring the bell; I must have my dinner”, Edmund simply and unostentatiously comes forward and does it himself, “preventing Fanny”4 (ch. 15).

After Sir Thomas’s return and the subsequent end of the play-acting project, Edmund makes sure to do Fanny justice. He tells his father that Fanny was in no way to blame. “Fanny … judged rightly throughout …. She never ceased to think of what was due to you. You will find Fanny everything you could wish” (ch. 20). If Edmund hadn’t taken the trouble to exonerate Fanny, Sir Thomas might have confounded her in the general blame. Fanny was too afraid of her uncle to have defended herself to him, and none of the others who were involved cared enough. Edmund, on the other hand, automatically takes it upon himself to help and champion Fanny.

Edmund takes the trouble to find out what Fanny wants. When Dr. and Mrs. Grant invite Edmund and Fanny to dine with them, it is a completely new attention to the latter. She is flurried by the unexpected application and unsure whether it is in her power to accept. Edmund, “delighted with her having such an happiness offered,” and first “ascertaining with half a look, and half a sentence” (ch. 22) that her only objection is on her aunt’s account, encourages her to accept. He explains the matter to his father who, of course, thinks it only right that Fanny should go. She is glad, for, to her, the engagement had “novelty and importance”. On another occasion of them dining at the Parsonage, Edmund begins to “quietly” fetch Fanny’s shawl “to bring and put round her shoulders” (ch. 25) in preparation for her departure. Though he never makes a show of it, his kindness to Fanny is constant.

Fanny’s brother William gives her a “very pretty amber cross” (ch. 26). Unfortunately, although he wanted to also purchase a gold chain for her to wear it on, he could not afford one, so she wears it on “a bit of ribbon”. Edmund takes note of this and decides to get her a chain himself. Presenting it to her, he explains, “I hope you will like the chain itself, Fanny. I endeavoured to consult the simplicity of your taste, but at any rate I know you will be kind to my intentions, and consider it, as it really is, a token of the love of one of your oldest friends.” (Ch. 27.) That he has paid attention to her tastes is obvious, for the chain is precisely what Fanny wished for. His kind action is accompanied by kind words, as well, as he assures her that he has “no pleasure in the world superior to that of contributing to yours. … no pleasure so complete, so unalloyed. It is without drawback.”

When Fanny rejects Henry Crawford’s proposal of marriage, Edmund attempts to show her “his participation in all that interested her” (ch. 34). When he sees her embarrassment, however, he endeavours to “scrupulously guard against exciting it a second time, by any word, or look, or movement.” Eventually, he thinks she must need at least the “comfort of communication” (ch. 35). He assures her that she has done exactly as she ought. Even though mistaken about Fanny’s thoughts and sentiments about Henry, he is observant of her feelings. Seeing “weariness and distress in her face”, he immediately resolves to “forbear all farther discussion; and not even to mention the name of Crawford again.” When other topics of conversation leave her still “oppressed and wearied”, he no longer tries to talk it away, but leads “her directly with the kind authority of a privileged guardian into the house” to rest.

Noah Webster, in his 1828 An American Dictionary of the English Language, defined “Kind” as “Disposed to do good to others, and to make them happy by granting their requests, supplying their wants or assisting them in distress; having tenderness or goodness of nature; benevolent; benignant.” Again and again, Edmund demonstrates this trait. Jane Austen’s heroes portray a variety of admirable qualities. Edward Ferrars and Colonel Brandon are both loyal and steadfast, Mr. Darcy is generous, Mr. Knightley is discerning, Henry Tilney is cheerful, Captain Wentworth is brave and industrious. I think, however, that Edmund Bertram’s trademark characteristic must be his unceasing, unassuming kindness.

_____________________________

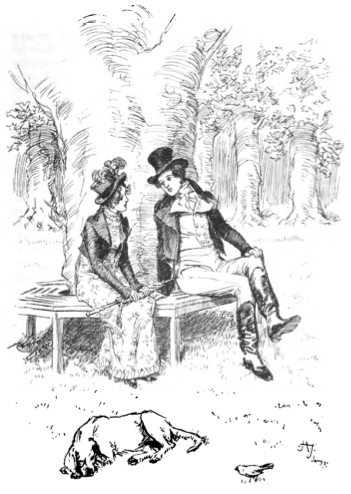

Illustration: “The kind pains you took to persuade me out of my fears” (Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, chapter 3) by C. E. Brock.

1. Not a strong girl, Fanny’s health did suffer from the loss of this regular, but not too strenuous, exercise: “Edmund was absent at this time, or the evil would have been earlier remedied.” (Chapter 4, italics mine.)

2. “Before the railroad, the horse was the way you got somewhere if you weren’t going on foot …. Horses were expensive both to buy and maintain …. In the 1820s, a good carriage horse or hunter could run £100 and even an ordinary hack could cost £25 to £40. Plus horses, unlike cars, had to be fed, sheltered, and cared for daily, which meant that if you got a horse you were also entering into a subsidy of the horse transportation business. You were buying the services of a corn dealer (fast horses ate 72 pounds of straw, 56 pounds of hay, 2 bushels of oats, and 2 bushels of chaff a week), a blacksmith, a saddler, a coachmaker (if you had a carriage), a harness maker, and — if you were fancy — a coachman and a groom as well.” — Daniel Pool, What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), pp. 142-143.

3. “Fanny was up in a moment, expecting some errand, for the habit of employing her in that way was not yet overcome, in spite of all that Edmund could do.” (Chapter 15, italics mine.)

4. According to Noah Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), the word “Prevent” has the meanings both of “To go before” and “To anticipate” (“Anticipate”: “To take or act, before another, so as to prevent him”).